By Kelly Hack

It was a normal Saturday morning for me. I woke up early and was watching Youtube videos in bed before my daily venture downstairs to make breakfast when I saw a new video from PBS Digital Studios, which releases a series of studies regarding certain facets of the literary world in a series called “It’s Lit!” It just so happened that on this day, they were discussing “Death, Personified.” I watched, in awe, as they listed the endless examples of authors crafting “Death” a physical character. I began to wonder: Why are writers so fascinated with death? I decided to launch a personal investigation and go in search of the truth behind this phenomenon.

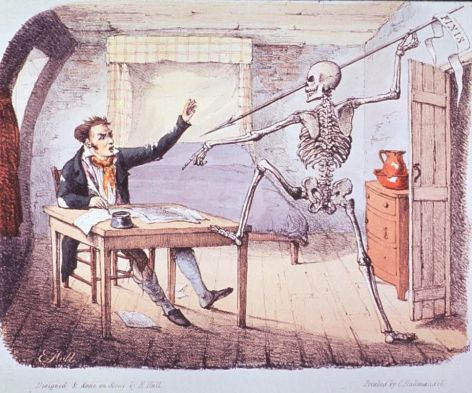

So I asked professors and graduate students in the CSUC English department, what about the theme of mortality makes it such a rich muse for writers? I began to notice a trend in their answers. Most agreed the use of death and its symbolism in literature is an inevitable constant. Professor Matt Brown, who focuses on American Literature and Culture in his courses, offered, “Death may be the only universal human experience and nobody in the world can tell us what it’s like.” In this way, Professor Brown believes personifying death gives readers a way to feel closer to understanding death as a whole, without having to experience it firsthand.

Grad student, Mary Gibaldi, who focuses on 20th-century American Literature and Feminist Theory, went a step further with her interpretation: “Not only is death an inevitable part of life, but it is often linked to other themes writers tend to gravitate towards power, identity, the social and socioeconomic spaces created after a person’s passing.” Upon speculation, these themes, in correspondence with one another, is what drives most plots in stories. Death, especially, serves as an unwanted change that forces the reader to be more open-minded and grow in some way.

Interestingly, Professor Jeanne Clark and Professor Rob Davidson, who both teach creative writing, gave a more poetic answer to the question. Clark reported, “It’s inevitability. The way it forces us to ask the hardest questions, to make meaning of suffering, to find consolation; it takes us to our edge. The ways it opens our hearts & minds.” Davidson added, “Surely the inescapable nature of our own demise—we are endlessly fascinated with questions of what death means, what happens after death, how death gives shape & meaning to our lives, and of course what one’s own death might mean: a reckoning, a release, an apocalypse, a rebirth.” The mere intricacy of these explanations adds the type of reasoning only a creative writer could offer. Somehow, their perspectives paint the concept of death as a vital and beautiful aspect of life.

Perhaps, in this way, it has managed to remain timelessly relevant in all genres of literature. While this question may never be truly answered, this at least gives me some idea about why writers remain fascinated with Death.

Faculty Recommendations:

Mary Gibaldi: Daniel Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone, Toni Morrison’s Beloved

Professor Matt Brown: There are dead bodies all over almost everything I read or teach. Leaves of Grass has 15 corpses in it and it is, by far, the most cheerful and optimistic text I teach. Nearly everyone dies in Moby Dick. And of course, the blues songs and Appalachian ballads I love so much are all populated by murderers and the murdered.

Professor Jeanne Clark: Elegy, Edward Hirsh; Elegy, Mary Jo Bang; The Duino Elegies, Rainer Maria Rilke; Brother, Matthew & Michael Dickman; Death Tractates & Bright Existence, Brenda Hillman; Trapeze, Deborah Digges; Prayer in Wind, Eva Saulitis

Professor Rob Davidson: Dante quickly comes to mind. Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. From more contemporary authors, I am enormously fond of George Saunders. His story “Sea Oak” is a zombie story in which a woman who, in her mortal life, was a passive pushover; as a zombie, she seeks lovers and adventure—death becomes, for her, an opportunity for a “do-over.” Sadly, it doesn’t work out, but Saunders’s moral is clear: carpe diem.